How human of me

Helpful thoughts for a life without drama

"How human of me"

Borrowed thought: How human of me

When I was introduced to the thought ‘How human of me” by Kara Loewentheil during a training seminar I was amazed at its effectiveness to generate self-compassion which is vital when we want to become and stay curious about our thoughts and feelings. But what does it mean to be human?

Etymology of 'human'

The word ‘human’ stems from the late Middle English humaine, from Old French humain(e), from Latin humanus, from homo ‘man, human being’ and is closely related to humane meaning having or showing compassion, inflicting the minimum of pain or a branch of learning intended to have a civilizing effect on people.

Biology and Philosophy

Approaching the question of what it means to be human leads us immediately to two categories: biology and philosophy. Looking at this from a biological level we may e.g. discover that humans are said possess a brain very large compared to our size, utilise bipedal upright motion to move about, lack fur, have a long childhood and see in colour (Wikipedia). Philosophy on the other hand, would prefer to seek an answer to the question of what being ‘humane’ entails. The thought ‘How human of me’ relates to both these viewpoints by recognising biological limitations to generate a sense of compassion for both us and others.

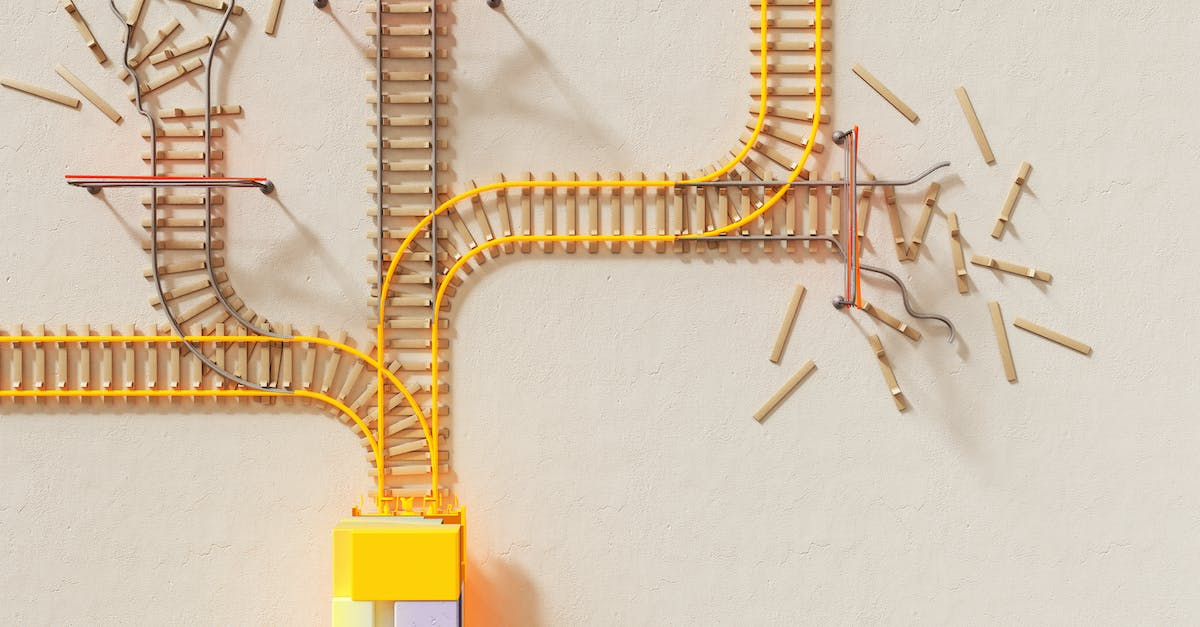

Perfectionism and the loss of an ensouled universe

The belief that everything is alive and has a soul (Panpsychism) was almost certainly widespread in pre-Socratic society and became popular again in the Renaissance after a decline in the Middle Ages. The rising interest in scientific enquiry in the 17th century, known as the Age of Enlightenment, paved the way for causal determinism which became the predominant way we view the world today wherein is assumed that the world is a determined clockworklike machine. René Descartes split the world into mind and matter, Isaac Newton found evidence to support this theory in physics and the French mathematician Pierre Laplace formulated and broadcasted the idea of determinism. The Industrial Revolution was a natural consequence of this way of thinking. With the invention of conveyor belt work, factories shot up in which the simple worker was just another cog in the ever-spinning machine, expected to work productively and efficiently at a constant, measurable level.

But we are not machines. Our productivity changes by day, season, environment, and age yet we expect a constant, machine-like output from us and others. Being reminded that we are biological beings disrupts the perfectionist fantasy that wants to convince us that that we should always perform at the same level and do everything perfectly.

Lucky mistakes

A by-product of the need to be constantly productive is the fear of making mistakes which is seen as unproductive and a failure. Yet, how can we ever learn or do something new without making mistakes? It just isn’t possible and realising that personal or professional growth is always accompanied by apparent setbacks fosters compassion.

An interesting aspect of this belief is also that ‘perfect’ is an inert state of being or doing. Only when we do things differently new discoveries are being made. When Pasty Sherman tried to develop a rubber material that would not break down from exposure to jet aircraft fuels, she discovered a stain resistant compound (Scotchgard) when dropping some of the mixture on her shoe. Not every mistake will necessarily lead to an invention, but it is helpful to keep in mind that they are not inherently bad and useless.

I am human

Compassion frees us from the lie that we are predictable, clockworklike beings and focuses our attention on universal human needs such as belonging and the search for meaning. To be human is stepping off the conveyor belt of unrealistic expectations and standing still, marvelling at the complex and diverse beauty of the world in all its expressions and circumstances.

Learn more about thought work:

https://schoolofnewfeministthought.com/the-society/